Often it is the personal memories of survivors of the Nazi terror regime that lead to the fact, that decades after liberation the fates of individual victims of the Nazi era are finally being dealt with. Especially in the case of the countless forced laborers who were exploited on the entire territory of today’s Austria, individual memories of individuals are of essential importance in order to make commemoration possible at all.

A reconstruction by Robert Obermair. Translated by Hilde Mayer

In contrast to concentration camp inmates, who were also present in many areas of Austria through various subcamps and work detachments, forced laborers were not only deployed in larger groups at the same time in one place, but in many cases were also assigned individually or in pairs to individual farms or small businesses. This small-scale scattering made it even more difficult after liberation to enable a local remembrance of these victims of the Nazi regime. Moreover, in the vast majority of cases, the profiteers of the forced labor system kept a veil of silence over the matter after 1945. In recent decades, at least some larger companies have started projects to deal with their own dark corporate history. The individual fate of those forced laborers who were exploited in agriculture or in small businesses, often alone in one place for many months or even years, remains hidden until today.

The individual fate of the forced laborers often remains hidden until today.

This would also be the case in the present case if Josef Duda, a surviving former Polish forced laborer, had not recorded his memories of the murder of his compatriot Josef Mandela at an advanced age for posterity with the help of his daughter. Supplemented by archival finds from the Nazi period or the immediate post-war period, these personal recollections allow us, on the one hand, to reconstruct the fate of a young Pole at the time of the Nazi regime in a small village in what is now Upper Austria and, on the other hand, to make the participation of the local population in the Nazi horror tangible.

Deported to the “Ostmark”

In the area around Schwanenstadt and Attnang-Puchheim (Upper Austria), numerous forced laborers were housed during the Nazi regime, especially on large farms. These mostly young men and women from various regions of Europe were exploited here day after day and lived in constant fear of being sanctioned with draconian punishments for the slightest misconduct. Nevertheless, it should also be noted at this point that the individual forced laborers were treated differently: While some families took them in like sons and daughters, on other farms they were treated like slaves. However, they were all largely disenfranchised.

The Pole Josef Mandela, born in 1921, had little luck with his “employer” H.[1]. Just 20 years old, he arrived in Landertsham – a small village between Attnang-Puchheim and Schwanenstadt – in April 1941 at the latest. Here, two neighboring farms had each been assigned a Polish forced laborer. We know relatively little about the first months of his work assignment, but further developments suggest, that he did not have an easy time of it from the start. On March 19, 1942, the situation escalated: on this day, Joseph Day, a peasant holiday, one of the two farmers gave the Polish forced laborer assigned there, Michał Radwański, the day off.

Radwański wanted to use the day off to pick up his friend Josef Mandela at the neighboring farmer’s house to visit two women friends of his who were deployed at another farm in Schwanenstadt. When Mandela saw that his friend had the day off, he also put away his pitchfork, went into the parlor and wanted to put on his new shoes (which he had bought himself). When farmer H., to whom Mandela had been assigned, also came into the room, he apparently wanted to take the latter’s shoes away. A brief scuffle ensued, whereupon Mandela left for Schwanenstadt, where he was arrested the next day by a local gendarme named Sandner. Mandela had been denounced by H., who claimed to have been threatened by him with a knife.

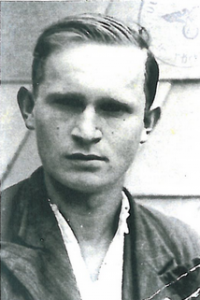

Josef Duda as a young man

Boring wait

Nothing happened for months. The local forced laborers did not know what had happened to Mandela, who had not been seen since his arrest. Half a year later, on December 23, 1942, the order suddenly came for the Polish forced laborers in the area to report to the police station in Schwanenstadt. After about 30 Poles had arrived there, they were searched; pocket knives, for example, were confiscated immediately. Afterwards, the forced laborers had to form a column and march out of the city in the direction of Attnang-Puchheim. The column was led by a machinist from the neighboring village of Altensam, who was armed with a carbine. Fear spread among the forced laborers. None of them knew what was going on and where they were headed. The column first moved along the railroad tracks to Tuffeltsham and then on to Landertsham. After passing H.’s farm, they went up a hill and down again on the other side. Here the police from Attnang-Puchheim were already waiting. Now came the order: “Wait!”.

After waiting for some time, two trucks and a car approached the group. When they arrived, an SS commando, a civilian Gestapo official, Mandela, and two other Poles got out of them. One of the SS men selected four of the assembled Poles. They had to carry a ladder, cords, two chairs and a coffin-like wooden box up the hill. In the middle of the meadow stood a pear tree. A rope with a noose was now attached to one of the tree’s branches. At the signal of the Schwanenstadt gendarme Sandner, the bound Mandela was forced – apparently amid laughter from the police officers present – to walk up to the tree. The two Polish prisoners, who had arrived earlier by SS truck, had to help Mandela up the ladder leaning against the tree, put the noose around his neck and pull the ladder away.

After the hanged man’s shackles had been removed, all the other Poles present, who had been waiting further down, were ordered up the hill. A Ukrainian interpreter from Schwanenstadt now had to translate the warning of one of the SS men into Polish that anyone who was guilty of something or who did not work would be hanged in the same way. When Mandela was subsequently brought down from the tree by one of the Poles, a pulse could still be felt, whereupon one of the SS men shot Mandela, who was already lying in the coffin. The coffin was then loaded back onto one of the trucks. While the Polish forced laborers from the surrounding area were driven back to their quarters, the two vehicles continued on to Frankenburg, where one of the two Polish prisoners who had been in the SS truck was hanged, but here without an audience. The other was also hanged the same day, presumably near Mondsee.

Lack of reappraisal

After the liberation in 1945, a Polish committee was founded in Vöcklabruck, which also tried to draw the attention of the Austrian authorities to Mandela’s execution. The Mandela case was subsequently investigated primarily by that same Polish committee, but without result. Not even the question of Mandela’s final resting place could be clarified. There were no consequences for the perpetrators involved. The denunciator H. apparently hid for two months, but otherwise remained unmolested. Sandner also went into hiding for a short time and was discharged from the gendarmerie in 1946, but was subsequently able to live unmolested in Attnang-Puchheim. On the other hand, one of the Poles present at the execution at the time, who had wanted to take revenge on H. and had entered his house, was arrested.

In Landertsham, too, it would be long past time to finally create a place of remembrance for Josef Mandela, who was murdered here – just 21 years old.

Otherwise, the matter was shrouded in silence. Even from the population of Landertsham, who – as a contemporary witness recalled – might have attended the execution, there was no initiative to commemorate the murder of Josef Mandela. So it was left to Josef Duda, who remained in the area after the liberation, to uphold the memory of his friend and compatriot. Josef Duda died in 2017, and with his generation the last witnesses who were able to keep the personal memories of their deported, maltreated and murdered friends and family members are currently leaving us. It is therefore all the more important that we not only try to secure the memories of these contemporary witnesses for future generations and make them accessible, but that we also enable a permanent commemoration at the historical sites of National Socialist acts of violence and terror.

In Landertsham, too, it would be long past time to finally create a place of remembrance for Josef Mandela, who was murdered here – just 21 years old – in the collusion of a local denunciator, a local gendarme and the SS and Gestapo.

[1] The name of the farmer is not shortened to protect the perpetrator, but because the files contradict each other regarding the name and his identity could not yet be definitively clarified.

Information on the author: Robert Obermair is a contemporary historian at the University of Salzburg and chairman of the board of APC.