In 1945, more than half a million Austrians were members of the NSDAP and thus actively supported the Nazi regime. The vast majority of them, however, did not have to bear any long-term consequences for this complicity after the end of the war – instead, coming to terms with their responsibility was left to their descendants.

A contribution by Hanna Frischenschlager. Translated by Hilde Mayer.

I grew up knowing that my grandfather was a National Socialist. His children, i.e. my mother and her siblings, never made a secret of it. Having hardly met him personally – he died in 1999, when I was only six years old, and we lived more than 200 km apart at the time – I formed my picture from what I had learned about Austrian history at school. National Socialists were therefore simply “bad people” for me.

Only recently, in the course of my history studies, did I have the opportunity to question this image of my grandfather in a more differentiated way. In a seminar paper on denazification in Austria after 1945, I worked on his biography. As a so-called “Minderbelasteter” – fellow traveler, he had been affected by measures against NSDAP members after the war. So, I researched archival documents, looked through photo albums, read biographies written by my grandparents in the 1980s, and had many conversations with family members. Step by step, I gained a better – albeit still hazy – impression of the person behind the documents and stories.

Childhood and youth during the war

My grandfather Leo Frischenschlager was born in Graz in 1910 as the fourth child of his parents and was baptized Catholic. His mother was a housewife, his father was a lawyer and also worked in agriculture. Later, Leo Frischenschlager described his mother as pretty, warm-hearted and fun-loving, his father in turn as a melancholic, irascible and withdrawn person. The children’s upbringing was marked by their father’s alcoholism and propensity for violence, which often led to heated arguments and punishment of the children. He and his siblings also had to experience hunger and scarcity – later, Leo Frischenschlager attributed his poor growth (he was only 1.68 m tall) to this malnutrition. Today, my mother and her siblings remember that throughout his life, their father always talked about the hunger he suffered in childhood. For example, he told them that out of desperation he sometimes ate moldy bread, bread with maggots, or even paper, just to have something in his stomach. But he also had fond memories of his childhood, such as the months the family spent in summer on an estate near Leibnitz: “The vineyard was a paradise for us children,” Leo Frischenschlager wrote about it in his 1988 curriculum vitae, “We spent three months there every summer during our elementary school years, were taken out of school earlier in the summer and got in later in the fall, which didn’t cause any problems in terms of learning.”

Relationship to National Socialism

Due to contradictory information in various files, Leo Frischenschlager’s attitude toward National Socialism is difficult to reconstruct. This is mainly due to the fact that his exculpatory statements after 1945 do not appear to be very reliable and that, moreover, he was hardly willing to talk about the events of the Nazi era within his family. He did, however, openly admit to his children that he was at least initially enthusiastic about National Socialist ideology and justified this with the hoped-for social improvements after Hitler came to power. As early as 1933, he sought admission to the NSDAP and made membership payments (with interruptions) during the period of Austrofascism despite the party ban. After graduating in law from the University of Graz in 1933, however, he joined the Vaterländische Front in 1935, which he later explained as a professional necessity: “[The] position as a judicial clerk in Graz [was] only possible by ‘crawling under’ the Vaterländische Front, an organization that I hated, but I had to join it, otherwise I would not have gotten the job.” After the “Anschluss” – “annexation” – of Austria, he applied for a NSDAP-membership in March 1938, joined the SA in 1939, and was finally accepted as a party member in 1943. This interest in the NS party probably had not only professional but also ideological reasons. Decades later, Leo Frischenschlager still occasionally used expressions such as “Fuehrer’s birthday,” “Reichsdeutsche” or “victors’ justice” to his children, which probably shows that he had deeply internalized Nazi thinking. Apart from that, however, there is – according to information from several Austrian archives – no evidence of his involvement in Nazi crimes. Leo Frischenschlager always emphasized to his children that during his work as a judge (1938-1943) he was never involved with death sentences or shootings, but only with ordinary criminal trials. This is also confirmed by documents from the Provincial Archives of Styria. For me, all these pieces of the puzzle rather add up to the picture of an opportunistic “fellow traveler” who hoped for professional advantages due to an NSDAP membership and supported the party program in principle, but ultimately remained relatively insignificant within the party hierarchy.

Denazification measures after 1945

In 1945, denazification was understood to be a comprehensive program aimed at removing Nazi ideology from the Austrian population and National Socialists from positions of power. This procedure was propagated above all by the American and British occupiers. Corresponding legal measures were implemented as early as April 1945, and 536,000 former NSDAP members were registered and sanctioned throughout Austria. Overall, however, denazification proceeded relatively smoothly, because the Austrian government’s priority in the post-war period was economic reconstruction, and punitive measures against its own population were only a hindrance to this. As early as 1947, the measures were largely lifted by several amnesty laws, and within a few years most National Socialists were able to return to their former positions. In individual cases, denazification nevertheless caused social hardship. For example, former National Socialists were the first to be called in when civil servants were dismissed, and the resulting existential difficulties were consciously accepted and regarded as a legitimate element of punishment.

Overall, however, denazification went relatively smoothly.

Leo Frischenschlager was also affected by this: in 1945 he returned to Graz from his wartime assignment in Hamburg (1943-1945) and was unable to return to his former profession as a judge. He was unemployed for several years and earned a small income by tutoring law students. My family members tell me today that he lived at subsistence level during this time. At the same time, it is no longer clear to me whether he suffered at that time primarily from his financial situation or rather from the serious illness of his wife. Inge Eichler had already been ill with tuberculosis before the wedding in August 1942 and had undergone a serious operation. After the end of the war, her condition worsened and she was admitted to a pulmonary sanatorium, where she died in April 1947.

Nazi past in the family memory

Despite this blow of fate, Leo Frischenschlager was eventually able to rise again to a respected social position. After the denazification measures had been significantly weakened at the end of the 1940s, he obtained a position as an articled clerk in Vienna in 1948 and shortly thereafter moved to Linz, where he was able to build up a successful law firm. In 1954, he married again and between 1954 and 1963 five children were born. In the long term, therefore, his support of the NSDAP did not have any adverse consequences for him – neither on the professional and financial level nor on the social level.

In the long term, his support of the NSDAP had no adverse consequences for him.

However, the effects of dealing with the Nazi past within the family were certainly noticeable. Even though Leo Frischenschlager’s party membership was never concealed, his parents hardly ever talked about the events before 1945. Political influence on the children was consistently avoided – presumably out of fear of negative consequences. Instead, only isolated, fragmentary stories from the Nazi era have survived today: For example, my grandfather told his children how he deserted from his base in Hamburg shortly before the end of the war and managed an “adventurous return” to Graz on a stolen bicycle. Furthermore, he also claimed that he had rejected Nazi ideology even before the end of the war and had therefore listened to the enemy radio station. Behind all these narratives, a careful focus can be discerned: while rebellious actions – however small – were particularly emphasized, one’s own role in the events of the Nazi era was left out. Similar narrative patterns are found in many Austrian families.

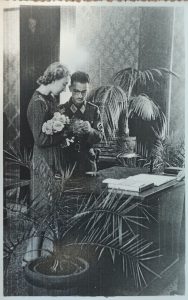

Wedding of Leo Frischenschlager and Inge Eichler in August 1942. © Private archive Frischenschlager.

Accordingly, my mother and her siblings only learned about many things very late. For example, they only found the wedding photos from 1942, in which my grandfather is wearing his SA uniform and swastika armband, shortly before my grandmother died in 2009. “He never said a word about that”, my mother said to me, concerned about it, “It was always all hidden”, my aunt said recently.

Memory from today’s perspective

When I think about my grandfather’s life today, I am torn between empathy and rejection. He supported a criminal regime that claimed millions of victims because – by all appearances – he hoped to gain professional advantages. On the other hand, I also feel a certain gratitude for his opportunism, without which my family would perhaps have a harder time today. In our conversations, the question of whether his party membership played a role in his deployment as a radio operator in Hamburg comes up again and again. Would he have been given this post if he had been less loyal to the regime, or would he have been sent to the front? At the same time, I feel compassion for the hardship that shaped so many 20th century biographies. I was born in the 1990s and grew up wealthy. Do I even have the right to judge his generation? Mixed in with all these considerations, however, is disappointment that the Austrian government failed to come to terms with the events of the Nazi era after 1945. If appropriate compensation had been paid at the time and long-term sanctions had been imposed, perhaps families like mine would be able to look back on the past with greater peace of mind today.

Information on the author: Hanna Frischenschlager studies history at the University of Salzburg and works as a freelance journalist.