Colleges and universities in Austria have traditionally been the forerunners of both scholarly and militant hostility toward Jews. Although the „Borodajkewycz Affair“ in 1965 represented an important turning point in the history of academic anti-Semitism, Alexander Pinwinkler argues in the following, that anti-Semitism is a politically mutable phenomenon and continues to exist in the academic milieu to this day.

(Translated by Hilde Mayer)

The scandal surrounding the Viennese economic historian Taras Borodajkewycz, who made no secret of his unbroken National Socialist convictions in his lectures at the then University of World Trade, shook the Austrian public in the mid-1960s. Among others, the cabaret artist Gerhard Bronner also played a role in this, adapting Borodajkewycz’s co-written anti-Semitic statements in his satirical TV program „Zeitventil“. The program was broadcast on March 18, 1965, and took the form of a fictional interview with the professor. His relevant remarks thus gained wider public attention. When Borodajkewycz held a press conference a few days later and proudly declared, to the applause of assembled fraternity members, that he had voluntarily joined the NSDAP at that time, the affair, which had been simmering for some time, escalated.

This led to demonstrations in Vienna’s city center, during which Borodajkewycz’s supporters and opponents clashed, sometimes violently. At one of these rallies on March 31, 1965, the then 67-year-old Ernst Kirchweger was knocked down by the right-wing extremist student Günther Kümel , who belonged to the Ring Freiheitlicher Studenten (RFS), and was so severely injured that he later died of his injuries two days later. Kirchweger, who had been a communist resistance fighter during the Nazi era, has since been considered the first political fatality in the history of the Second Republic. Approximately 25,000 people took part in the following silent march, with which official Austria declared its support for anti-fascism. Kümel was sentenced to ten months in prison in October 1965. Borodajkewycz, who had triggered the affair with his statements, was forced into retirement with full pay in 1966.

1965: Demonstration against Taras Borodajkewycz © Barbara Pflaum / Imagno / picturedesk.com; APA 19650330_PD0003 (RM)

The „Borodajkewycz Affair“ caused a sensation not only in Austria itself, but also internationally. It prompted the eminent jurist Hans Kelsen to reject the University of Vienna’s invitation to participate in the celebrations of its 600th anniversary. He was only persuaded with difficulty to still come to Vienna as a guest of honor of the federal government. Kelsen was the co-author of the democratic constitution of 1920, who had emigrated from Austria and had himself been targeted by Borodajkewycz’s anti-Semitic diatribes. In 1967 he was awarded an honorary doctorate from the University of Salzburg, which his biographer Rudolf A. Métall accepted on Kelsen’s behalf.

Anti-Semitism at Austrian Universities – a sinister tradition

In 1993, the U.S. historian Bruce F. Pauley attested that Austrian anti-Semitism was „a kind of national tradition“. It was favored by the influence of the Catholic Church, which shaped culture and mentality, by the economic and social development, which was late in comparison with other countries, and by the predominantly rural and small-town population structure, as well as by the weakness of liberalism.

In the last decades of the 19th century, traditional Christian anti-Judaism in Austria was overlaid and radicalized by racist anti-Semitism. In particular, the Christian Socialist mayor of Vienna, Karl Lueger, agitated around 1900 as a catalyst for the latent hostility against Jews. Anti-Semitism was expressed in agitation and propaganda, but there was no corresponding government action in the monarchy. The surgeon Theodor Billroth had already advocated a scientifically dressed anti-Semitism in his work „On the Teaching and Learning of the Medical Sciences at the Universities,“ published in 1876, in which Billroth characterized the „Hungarian and Galician Jews“ as „strongly degenerated“ and heading toward „mental and physical depravity.

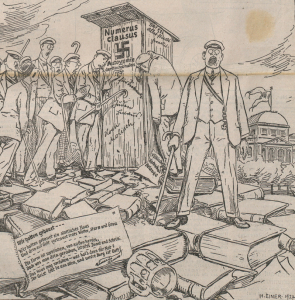

„Die Wacht am Numero Clausett,“ folk-Nazi caricature, 1927

The ethnic student fraternities enthusiastically took up this supposedly scientifically based anti-Semitism and put it into practice in the form of Aryan paragraphs, which they included in their statutes. The Viennese „Libertas“ made a start, refusing Jews admission to its fraternity as early as 1878. In 1887, the German nationalist politician Georg von Schönerer described anti-Semitism in the Reichsrat „as a cornerstone of national thought,“ indeed, „as the greatest national achievement of this century“ in general.

„Beating terror under the cover of academic immunity“.

At universities and colleges, the ethnic-german-national fraternities were so militant against dissidents and Jews after the First World War that as early as 1921 there was talk in the National Council of their „terrorist rule“. The writer Stefan Zweig dedicated several paragraphs in his autobiography „Die Welt von gestern“ (The World of Yesterday) to the ethnic corps students „who, under the protection of academic immunity, established a beating terror without equal“. As late as 1962, this beating terror was downplayed in a fraternity commemorative publication as „friction with East Jews“. The universities had been „flooded by East Jews“ and one had had to take action against the „Bolshevik danger“.

The violent corps students were not alone at the universities, however, for they enjoyed the partly open, partly covert support of large sections of the professoriate. In 1930, for example, the rector of the University of Vienna, Wenzeslaus Graf Gleispach, ensured that a new student law „on the basis of national law or German-Aryan law“ was introduced, which was to divide the students into four „nations. Accordingly, the „non-German (Jewish)“ „nation“ joined the „German“ one. Separate categories were provided for the „mixed“ as well as „other“ student nations. Although the Constitutional Court annulled Gleispach’s „student regulations“ in June 1931, Gleispach had already sent out an anti-Semitic signal well before the National Socialists seized power in Germany, which had a politically disastrous after-effect. In addition to open anti-Semitism, which aimed to discriminate against students stigmatized as Jewish, there were also covert circles of anti-Semitic and German nationalist professors. For example, from the early 1920s onwards, members of the „Bear’s Den“ network ensured through interventions and agreements that Jewish or politically left-wing scientists were not habilitated or appointed at the University of Vienna. The mass expulsion of Jewish students and teachers at Austrian colleges and universities in the course of the Anschluss in 1938 thus had a prehistory that the National Socialists could easily build on.

The former School of World Trade in Vienna Döbling

Anti-Semitism at Austrian Universities after the „Borodajkewycz Affair“ – a marginal phenomenon?

In the decades after 1945, the Austrian state doctrine of the „victim thesis“ played a significant role in the widespread lack of coming to terms with the anti-Semitic excesses at universities and colleges during the interwar and Nazi periods. This not only led to the fact that after the judicial-bureaucratic denazification was completed, many former Nazi party members among the professors returned to academic offices and dignities. It also meant that in the post-war period it was often impossible for expelled and emigrated academics to regain their former professional positions.

„The state doctrine of ‚victimhood‘ played a significant role in the failure to come to terms with anti-Semitic excesses“

Anti-Semitic attitudes and stereotypes were widespread among the Austrian population even after the political break in 1945 and were sometimes openly communicated. Only gradually was anti-Semitism made taboo in the public sphere and interpreted as a marginal right-wing phenomenon. Anti-Semitic beliefs shifted to certain codes even in official statements – such as those symbolized allusively by the terms „East Coast“ or „Wall Street.“ The overtly racist version of anti-Semitism, on the other hand, largely lost influence. „Race-theoretical“ justifications of anti-Semitic thought and action were mostly reserved for a few German nationalist fraternities, which continued to uphold the „Arierparagraph“ even after 1945.

Twenty years after the end of the Nazi terror, the „Borodajkewycz Affair“ led to a first important turning point, both in terms of higher education policy and among the broader public. The debate about Borodajkewycz was essentially driven by critical students. It provided the first discussion of the involvement of Austrian society in National Socialism. This scandal also had the effect of significantly reducing right-wing extremism at Austrian universities, and the student politics of the neo-Nazis largely lost significance.

In this context, it should also be pointed out that a specifically „left-wing“ anti-Zionism, which is not always easy to separate from manifest anti-Semitism, has not been without resonance on the political left inside and outside universities since the 1960s and 1970s. In the „New Left,“ anti-colonial and anti-imperialist positions were combined with anti-Zionism and pro-Palestinian commitment. On the other hand, anti-Semitism was and still is fought within this scene. It is thanks to this commitment, for example, that anti-Semitic campaigns such as „Boycott – Divestment – Sanctions“ (BDS), which denounce Israel as an „apartheid state,“ have so far hardly been able to gain a foothold in Austria. However, every new escalation of the Middle East conflict shows how quickly even left-leaning political groups can fall back into stereotypical anti-Semitic patterns.

The latter also applies to the political center that sees itself as „bourgeois,“ as has recently become clear at the University of Vienna in recent years. For example, we need only recall the scandal that became public in 2017 surrounding functionaries of the VP-affiliated Aktionsgemeinschaft (AG) at the Vienna Juridicum, who exchanged anti-Semitic and inhuman „jokes“ in secret chat groups. And in the fall of 2019, it became publicly known that students of the physics faculty at the University of Vienna had sought a more than questionable „pastime“ with „jokes“ about the Holocaust, rape and disabled people as well as incitement against minorities in WhatsApp groups that had at least 80 members.

The conclusion that must be drawn from this is obvious: Open anti-Semitism at Austrian universities and colleges may no longer be an official policy today. However, hostility towards Jews in its most diverse forms is still rampant at academic educational institutions. It is thus not a historically „closed“ chapter. Rather, it must be kept in mind more than ever before as a changeable phenomenon that is widespread in all social and political groups and educational strata, and it must also be clearly combated.

Literature

Embacher, Helga/Bernadette Edtmaier/Alexandra Preitschopf: Antisemitismus in Europa. Fallbeispiele eines globalen Phänomens im 21. Jahrhundert, Wien-Köln-Weimar 2019.

Pinwinkler, Alexander: Die „Gründergeneration“ der Universität Salzburg. Biographien, Netzwerke, Berufungspolitik, 1960-1975, Wien-Köln-Weimar 2020.

Taschwer, Klaus: Hochburg der Antisemitismus. Der Niedergang der Universität Wien in der ersten Hälfte des 20. Jahrhunderts, Wien 2015.

Information on the author: Alexander Pinwinkler is a private lecturer in contemporary history at the University of Vienna and a lecturer at the University of Salzburg